Between 2002 and 2005 scientific, policy and regulatory aspects of contaminated sediments and dredged material were addressed in 17 workshops and 3 conferences organized by SedNet. Europe’s leading scientists and major sediment managers contributed to these SedNet activities. The results are summarized below. This text equals the extended summary from the SedNet booklet “Contaminated Sediments in European River Basins”.

• Sediment

• It’s value

• Contamination

• Adverse effects of contamination

• Dredged material management

• Legislation and guidance

• Sediment management challenges

• Quality issues

• Quantity issues

• Management options

• Recommendations

Sediment

Sediment is an essential, integral and dynamic part of our river basins. In natural and agricultural basins, sediment is derived from the weathering and erosion of minerals, organic material and soils in upstream areas and from the erosion of river banks and other in-stream sources. As surface-water flow rates decline in lowland areas, transported sediment settles along the river bed and banks by sedimentation. This also occurs on floodplains during flooding, and in reservoirs and lakes. Often the natural sedimentation areas are severely restricted, e.g. because of embankments and the loss of flooding areas as a result of these embankments. At the end of most rivers, the majority of the remaining sediment is deposited within the estuary and in the coastal zone. Natural river hydrodynamics maintain a dynamic equilibrium, regulating small variations in water-flow and sedimentation by re-suspension and resettlement. In estuaries, sediment transport occurs both downstream and upstream, mixing fluvial and marine sediment as a result of tidal currents.

Its value

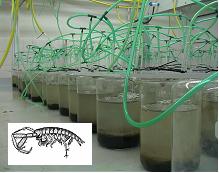

Sediment forms a variety of habitats. Many aquatic species live in the sediment. Microbial processes cause regeneration of nutrients and important functioning of nutrient cycles for the whole water body. Sediment dynamics and gradients (wet-dry and fresh-salt) form favorable conditions for a large biodiversity, from the origin of the river to the coastal zone. A healthy river needs sediment as a source of life. Sediment is also a resource for human needs. For millennia, mankind has utilized sediment in river systems as fertile farmland and as a source of construction material.

Contamination

Sediment acts as a potential sink for many hazardous chemicals. Since the industrial revolution, human-made chemicals have been emitted to surface waters. Due to their properties, many of these chemicals stick to sediment. Hence in areas with a long record of sedimentation, sediment cores reflect the history of the pollution in a given river basin. Where water quality is improving, the legacy of the past may still be present in sediments hidden at the bottom of rivers, behind dams, in lakes, estuaries, seas and on the floodplains of many European river basins. These sediments may become a secondary source of pollution when they are eroded (e.g. due to flooding and channel bank erosion) and transported further downstream.

Along the course of the river to the sea, transportation, dilution and redistribution of sediment-associated contaminants occurs. Many relatively small inputs, all complying with emission regulations, accumulate to reach higher levels by the time sediment reaches the river delta. In the estuary, uncontaminated marine sediments are mixed with contaminated fluvial sediments. This natural ‘dilution’ decreases contamination level in a gradient towards the sea over short distances, but does not alter the actual transported quantity of contaminants.

Despite regular sediment quality assessment by member states, a reliable estimation of the overall amount of contaminated sediment in Europe is hard to give. The main reason for this is the absence of uniformity in sampling methods, analytical techniques and applied sediment quality standards or guideline values. This causes a lack of inter-comparability. Typically, countries along the same river basin use different methods.

Adverse effects of contamination

Contaminants can be degraded or fixed to sediment components, thus decreasing their bioavailability. At a certain level, contaminants in sediment will start to impact the ecological or chemical water quality status and complicate sediment management. In the end, effects may occur such as the decreased abundance of sediment dwelling (benthic) species or a decreased reproduction or health of animals consuming contaminated benthic species. Contaminated sediments remain potential sources of adverse affects on water resources through the release of contaminants to surface waters and groundwater. Furthermore, contamination adversely effects sediment management, as handling of contaminated material, e.g. in the case of dredging, is several times more expensive than handling clean material.

Contaminants can be degraded or fixed to sediment components, thus decreasing their bioavailability. At a certain level, contaminants in sediment will start to impact the ecological or chemical water quality status and complicate sediment management. In the end, effects may occur such as the decreased abundance of sediment dwelling (benthic) species or a decreased reproduction or health of animals consuming contaminated benthic species. Contaminated sediments remain potential sources of adverse affects on water resources through the release of contaminants to surface waters and groundwater. Furthermore, contamination adversely effects sediment management, as handling of contaminated material, e.g. in the case of dredging, is several times more expensive than handling clean material.

Clean sediment can also have environmental and socio-economic impacts. For instance, turbidity and excessive sedimentation have a physical effect on benthic life, too much sediment in navigation channels requires costly dredging, and sedimentation behind dams decreases the economic lifetime of that dam. Furthermore, dams decrease the supply of sediment needed to support downstream wetlands, estuaries and other ecosystems. SedNet focused on contamination issues, rather than on such sediment quantity issues.

For the assessment of contaminated sediment, there is not one ‘best’ method available. Each specific management question requires a tailor-made solution. Chemical analysis can be used to determine concentrations of selected hazardous chemicals and then it can be checked if the concentrations exceed pre-defined standards or guideline values. The toxic effects of sediment on organisms can be tested by using bioassays. Through a field inventory the long-term impact on sediment biota can be investigated. These assessment methods (chemical, bioassay, field) are complementary by giving a unique answer that cannot be given by any of the individual methods by themselves. But each method also has its own unique drawbacks and uncertainties.

Many water and port managers face the continuous effort of dredging in order to maintain the required water depth. Europe-wide, the volume of dredged material is very roughly estimated at 200 million cubic meters per year. There are three types of dredging: capital, maintenance and remediation dredging. Capital dredging is for example for land reclamation, deepening fairways, etc. Maintenance dredging is mainly to keep waterways at a defined depth to ensure safe navigation, and remediation dredging is to solve environmental problems of contaminated sediments. Contamination mainly leads to problems in maintenance dredging because given standards or regulations do not allow the free disposal in the aquatic system. In general with capital dredging old, uncontaminated sediments are being dredged. There is a lot of information on the different options of dredged-material management available.

Dredging is mainly done in the coastal or marine environment. Therefore, international guidance has existed for many years to minimize the ecological effects of dredging and open water disposal. European legislation for handling dredged material is complex, because dredged material is at the borderline of water, soil and waste policies. European legislation affects the management of dredged sediments in upland areas, like the waste legislation, especially the EU Landfill Directive, and possibly the Habitats Directive, amongst others. These EU legislations do not (as yet) deal adequately with sediment.

The EU Water Framework Directive (WFD), in force since the year 2000, does not specifically address sediment management. But it can be a tool to tackle the sources of sediment contamination. It offers an opportunity to further improve our knowledge about the relation between sediment quality and water quality and to harmonize quality assessment and sediment management on a river-basin scale.

Sediment management challenges

Sediment and dredged-material management challenges and problems relate to quality and quantity issues. Quality issues relate to contamination, legislation, perception, risk-assessment, source control and destinations of dredged material. Quantity issues mainly relate to erosion, sedimentation, flooding, the effects of damming and the resulting morphological changes downstream. Often quantity and quality aspects are interrelated: the overall umbrella is the river basin.

Quality issues

The management of contaminated sediments in Europe has been mainly the direct concern of authorities dealing with navigable waterways. Contamination can inflict severely the management of dredged sediments. The costs for the removal of excess sediment increases when it is too contaminated for unrestricted relocation. Port managers are concerned that they have to bear the extra costs for managing contamination which is derived from contributions along the river basin. The ‘polluter pays’ principle is far from being applied. The problem is left for the problem owner and there is no link to those that have caused it.

Besides complicating dredging activities per se, contaminated sediment may pose ecological risks or risks to water quality. The relation between sediment quality and risks is complex and site specific, requiring assessment methods based on bioavailable contaminant fractions and bioassays rather than results based on the traditional total contaminant concentrations. However, if sediment quality impairs the chemical or ecological status, remediation measures may be needed. So far, only in a few Member States has contaminated sediment been managed due to its impact on the ecological quality of water bodies.

An integrated approach for sediment management is presently lacking. The WFD aims at source reduction which in the long term may lead to ‘clean’ sediment quality. Next to the emissions of point and diffuse sources, a source of increasing importance in this respect is historic contamination, i.e. our legacy of the past. The diffuse sources in which such contamination is present in many European basins are becoming increasingly important. Even more now, since the risk of extreme river floods, that may wash the hidden pollution into the water system once again, seems to have been underestimated in the past.

Last but not least, climate change and its impacts on the hydrology at the river-basin scale will affect sediment fluxes and should be anticipated in a sediment management plan.

Costly end-of-pipe solutions may be unavoidable for sediment and dredged-material management. Solutions like relocation into the aquatic system or placement on river embankments are the first options to consider, since they bring the sediment back to where it belongs. But these solutions are only acceptable if the contamination is below given standards. Depots for contaminated dredged material can be an option in this situation, but they are expensive, often lack public acceptance and are subject to complex legislation.

Alternatives include treatment for beneficial use and controlled (confined) disposal. Treatment and re-use is politically encouraged, but is currently applied only at a small scale because of the higher costs compared to disposal and the lack of product markets. However, in some cases treatment and beneficial use may be a competitive alternative for confined disposal. Confined disposal will remain the first choice solution for the time being. For the realization of new confined disposal sites (both upland and sub-aquatic), public involvement and support are needed. In many cases the procedures are very time consuming (10-15 years) and/or the lack of public acceptance can complicate matters and their implementation.

| Recommendations The main recommendations resulting from the SedNet activities towards European policy development, sediment management and research, respectively, are: | |

| • | Further develop and eventually integrate sustainable sediment management into the European Water Framework Directive |

| • | Find management solutions that carefully balance social, economic and environmental values and are set within the context of the whole river system |

| • | Improve our understanding of the relation between sediment contamination (hazard) and its actual impact to the functioning of ecosystems (ecological status) and develop strategies to assess and manage the risks involved |

| More specific recommendations are given in Chapter 6 of the SedNet booklet (pdf, 8.5 MB). | |